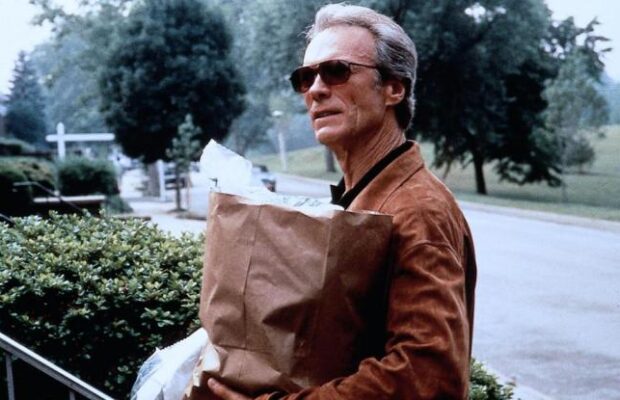

REVIEW: The Mule (2018)

Run Time: 116 Mins

Rated: R

What To Expect: More classic Clint Eastwood.

2018’s The Mule is the latest motion picture undertaking for Clint Eastwood as both director and actor, denoting his first big screen appearance since Trouble with the Curve back in 2012. Eastwood is surely one of the oldest filmmakers to pull off the double duty, yet he still has what it takes on both sides of the camera. With a screenplay by Gran Torino scribe Nick Schenk, The Mule is not the white-knuckle thriller implied by the marketing, but instead a pensive, often humorous character study that’s not for all tastes. Admittedly, the narrative does consist of spare parts, incorporating clichéd story beats as well as familiar themes involving family and redemption, treading similar thematic ground as Gran Torino. Nevertheless, The Mule works in spite of the clichés, thanks in large part to Eastwood’s astute, resolutely old-fashioned handling of the material.

A horticulturist in his late eighties, Earl Stone (Eastwood) was once hugely popular in his local community with a thriving plant business, but internet competition forces him to close up shop. Destitute and with nowhere to go, Earl tries to attend the engagement party of granddaughter Ginny (Taissa Farmiga), but his ex-wife Mary (Dianne Wiest) and estranged daughter Iris (Alison Eastwood) are unable to overlook the years of neglect, with Earl perpetually prioritising work over family. An opportunity presents itself, however, when Earl is approached by somebody connected to a Mexican cartel – he can earn many thousands of dollars working as a drug mule, with his spotless criminal record and cautious driving deflecting suspicion. Even though Earl only intends to complete a single run, he’s constantly drawn back, with his success earning him the respect of cartel boss Laton (Andy Garcia). As the shipment amounts increase, Earl makes a fortune for himself, using the money to save his home, help local businesses and spoil Ginny, working to turn his life around. However, hotshot DEA Agent Colin Bates (Bradley Cooper) is desperate to make a bust, working with partner Trevino (Michael Peña) to stifle the cartel’s drug deliveries by intercepting their primary mule.

Playing out like a fable, The Mule is loosely based on the true story of Leo Sharp, a World War II veteran who became a cartel drug mule in his eighties. There is a reason Sharp’s name is not retained, as this is not a biopic and the narrative is largely fictitious, giving Eastwood and Schenk free rein to both have fun with the story, and introduce drama to make the picture more compelling and dramatically satisfying. As per usual for an Eastwood movie, The Mule is deliberately leisurely in terms of pacing, but it’s nevertheless compelling thanks to well-judged editing by Eastwood regular Joel Cox. Perhaps another editor could have taken the movie down to a tauter runtime, but many of The Mule‘s charms derive from its unhurried nature, lingering on details and moments that other filmmakers would exclude. Not everything works, however. With Eastwood known for shooting first drafts and sticking closely to the script, The Mule does at times feel like a first draft in need of a polish, or a workprint waiting for some minor reshoots and trimming. Some dialogue is noticeably on-the-nose, including Ginny chastising Earl late in the picture, while scene transitions feel slightly skewiff at times, and the cartel is abruptly forgotten about at the end, with Schenk seemingly unsure about how to provide any closure on that front. Nevertheless, these are minor complaints.

Like Gran Torino, The Mule is unexpectedly humorous, earning more laughs than virtually any comedy released throughout 2018. However, the comedy is character-based, with Earl casually wielding offensive terms or simply saying unexpected things, though there is no malice behind what he says. Indeed, Earl is not exactly racist; he just has no filter and never adjudged to today’s sensitive, politically correct world. Hell, Earl makes friends with several Mexican cartel members, and chooses to help an African-American couple with a flat tyre. Additionally, Earl encourages cartel members to actually enjoy life as he comprehends his shortcomings as a husband and father, realising the importance of family and even warning Bates not to make the same mistakes as him. Although familiar, this material does add dramatic heft to the movie, preventing it from feeling soulless or hollow. In different creative hands, The Mule could have been a PG-13 affair, but Eastwood uses the R rating to accommodate salty dialogue and infrequent bursts of brutal violence, bestowing the movie with flavour and credibility. Furthermore, this is Eastwood’s first collaboration with cinematographer Yves Bélanger (replacing Tom Stern, who shot every Eastwood project since 2002’s Blood Work), who gifts The Mule with terrific visual vitality, while one could be forgiven for assuming that Arturo Sandoval’s effectively low-key original score was composed by Eastwood himself.

Unsurprisingly for a Clint Eastwood production, The Mule features a stellar cast of recognisable performers, all of whom are effective in their respective roles. Earl Stone represents another idiosyncratic character for the 88-year-old actor, who unleashes his trademark growl and badass disposition once again. Eastwood actually plays the role rather gently throughout the movie’s early stages, relying more upon his softer voice, but as Earl finds himself drawn deeper into dangerous territory, there’s a subtle shift in the performance as the character displays more grit. Chief among the joys of watching The Mule are scenes in which Earl sings along to classic tunes as he drives along the motorway, often forgetting the lyrics and singing off-time. In the supporting cast, Cooper is expectedly charismatic and captivating as Bates, while Peña makes a positive impression despite not having a great deal to do, and Laurence Fishburne is reliably solid as a DEA Special Agent. Also worth mentioning is Taissa Farmiga (The Nun), who’s wholly believable in a small but important role. Beyond that, Eastwood’s own daughter Alison is on hand to play Earl’s daughter which gives the movie some authenticity, while two-time Academy Award winner Dianne Wiest is predictably strong as Earl’s ex-wife. It’s a treat watching the interplay between Wiest and Eastwood, and their late scenes together are genuinely touching.

In Eastwood’s hands, The Mule is not needlessly dour or boring – on the contrary, the movie is seriously enjoyable and even rewatchable, making it a must-watch for fans of the director/actor. The easily offended will likely take issue with some of the dialogue, or with Earl’s relentless womanising, but The Mule is a breath of fresh air precisely because it is not watered down for mass consumption. Gran Torino represented a thematically perfect end for Eastwood’s acting career in 2008, and it is somewhat of a shame that it did not remain his final screen appearance. Nevertheless, The Mule is a more fitting end than the nothing-special Trouble with the Curve, and it’s always a pleasure to see Clint on the big screen. It is also encouraging that Clint did not finish his directorial career with The 15:17 to Paris.

11 Comments